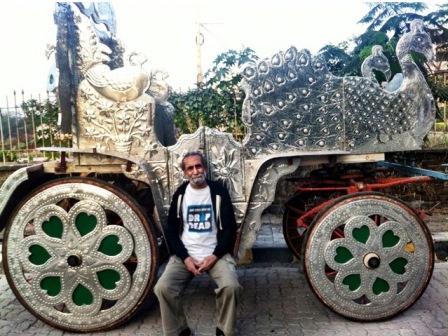

We chat with DNA’s chief cartoonist Manjul on cartooning in today’s times, the journalism space, and coming to work without a clue.

by Vrushali Lad | vrushali@themetrognome.in

In the early 1990s, a class 11 boy went to the Dainik Jagran offices in Kanpur and applied for a cartoonist’s job. “I had no idea that nobody is there at newspaper offices at 12 noon. There were just a few features guys there and I met the features editor. She asked me to leave my work there and they would get back to me.”

He returned the very next day for a reply. “I was determined to be a newspaper cartoonist when I was in class 8. But the editor told me she couldn’t employ me. She had shown my work to one of the artists at the newspaper, who felt that my ‘lines had no power’ and stuff like that – which may have been true, because I was very young, and my drawing used to be terrible when I was younger. I was disappointed, but to my good luck, I bumped into Rajani Gupta (one of the owners) on my way out, and I had met her only the previous day for the first time. I told her that I hadn’t got the job, but she got it for me,” he grins.

Now, over two decades later, he is the chief cartoonist at Daily News & Analysis (DNA), a position he has held since the paper’s  inception in Mumbai in 2005. Manjul, the only part of his name he is willing to give (even his visiting card reads ‘Manjul, Chief cartoonist’), says he was hired because DNA’s owners wanted to ‘revive the dying art of cartooning’. “I feel that DNA has done journalism a big service by carrying cartoons daily,” the 40-year-old says, explaining that in 2005, the city’s newspapers, even the The Times of India, did not have cartoons in their pages. “Only Mid Day had cartoons by Ponnappa and Morparia. DNA introduced cartoons under ‘Nobody’s business’ in its DNA Money edition. It was a great chance for me to be part of the biggest product launch since independence and have a dedicated cartoon slot in the paper’s pages,” he says with quiet pride.

inception in Mumbai in 2005. Manjul, the only part of his name he is willing to give (even his visiting card reads ‘Manjul, Chief cartoonist’), says he was hired because DNA’s owners wanted to ‘revive the dying art of cartooning’. “I feel that DNA has done journalism a big service by carrying cartoons daily,” the 40-year-old says, explaining that in 2005, the city’s newspapers, even the The Times of India, did not have cartoons in their pages. “Only Mid Day had cartoons by Ponnappa and Morparia. DNA introduced cartoons under ‘Nobody’s business’ in its DNA Money edition. It was a great chance for me to be part of the biggest product launch since independence and have a dedicated cartoon slot in the paper’s pages,” he says with quiet pride.

Drawing on life

Manjul’s parents were unhappy with his chosen vocation, but that didn’t stop him from working at a newspaper. “I was studying Science. They thought I was ruining my future, a very middle-class concern. My father would say that I would make more money selling potatoes! Later, I ‘ruined’ my brother’s career – he followed me into journalism!” he laughs.

Manjul’s parents were unhappy with his chosen vocation, but that didn’t stop him from working at a newspaper. “I was studying Science. They thought I was ruining my future, a very middle-class concern. My father would say that I would make more money selling potatoes! Later, I ‘ruined’ my brother’s career – he followed me into journalism!” he laughs.

He didn’t have a background in drawing – “I think I got it from my mother, whose drawing was very good” – and at his first job, he quickly learnt that repetition honed his skill. “We didn’t have computers in those days, so if there was any redoing to be done, you had to do the cartoon all over again. But on paper or on the screen, I find that drawing again and again only makes the cartoon better,” he explains.

Though thrilled with the chance to work with a behemoth like Dainik Jagran , he realised that he didn’t want to be stuck doing comic strips. “I wanted to do serious political cartoons. Soon I moved to a daily newspaper for a while, before going to a newly-launched paper in Lucknow in 1992.” He loved his time in a new city, learning from and mingling with several senior journalists.

“I understood that you can’t become a cartoonist just by drawing well. You must assess what you are trying to say, and your reader must instantly grasp your meaning.” But he had to quit the job in 1996. “I was offered a bribe for not drawing against chief minister Mulayam Singh Yadav. I ignored it for a while, till one day my editor told me not to draw a cartoon against him, when I decided to move to Delhi.”

Computers and cartoons

He was probably among the first cartoonists in the country to draw on a computer. “Dainik Jagran got a computer before everyone else. I familiarised myself with it, working on an extremely slow vector drawing software. But you couldn’t control everything on it, and drawing by hand was faster,” he laughs. “Later in Lucknow, when the paper became a colour paper, I used my skills to draw by hand, scan the drawing and colour it by hand again.

When I first told the processing team that we could do the colouring work at the office, they didn’t believe me. I persisted, saying that they could make separate CMYK plates, and when they tried it, the colours came out well,” he explains.

English press, ahoy!

Manjul was lucky to get a break into the mainstream English press when he bagged a cartoonist’s job at The Financial Express in 1996, where Prabhu Chawla was the editor. “It was a big deal to come from the Hindi press and get a job with a big English paper. A year later, I moved to India Today after he (Chawla) moved there. They were technically the most advanced, and I got the chance to use a stylus there for the first time.”

Manjul was lucky to get a break into the mainstream English press when he bagged a cartoonist’s job at The Financial Express in 1996, where Prabhu Chawla was the editor. “It was a big deal to come from the Hindi press and get a job with a big English paper. A year later, I moved to India Today after he (Chawla) moved there. They were technically the most advanced, and I got the chance to use a stylus there for the first time.”

The only difference between using a paper and a stylus was the hand-eye synchronisation with the latter. “But the stylus saves a lot of time,” he says.

Throughout all of this, he was learning just how impactful his job could be. “Observation is a big part of a cartoonist’s job. I still struggle every day, it’s never easy. I come to work with no ideas. Often I find that five cartoonists are saying the same thing, in slightly different ways. The best cartoons make fun of somebody without him realising that you are making fun of him.”

Working and networking

Journalists, whether reporters or cartoonists, must work for their readers. “A journalist is only as good or bad as their editor,” he says. Another consideration is the reach and speed of social networking in disseminating information. “Every time people retweet my cartoon, it scares me. It puts additional pressure on me to top my last effort,” he says. “But I must point out that social networking gives people a reference point. To understand a cartoon, you must be aware of the background information. Social networking has actually made my job easier, it makes so much information available that you are never out of ideas,” he explains.

He feels that Facebook and Twitter help him gauge readers’ thought processes, but he doesn’t want to be addicted. “So many editors are constantly tweeting. When do they read their papers, when do they prepare their editions? Also, so many print journalists tweet some really interesting things, but their published stories are rubbish. You can’t take social networking so seriously,” he says.

His story today

He says that the exposure with Hindi newspapers is tremendous, with higher circulation and readership, but he has been happier with editors in the English press. “An editor’s job is to pull you back when your cartoon is too harsh, and I welcome that. Freedom of expression comes with certain boundaries.”

He adds, “Cartoons are art. Art ceases to exist when something is created just to irritate somebody. Cartooning is not about insulting or unnecessarily provoking somebody. Bad cartoons are those that insult, that are created just to prove that you can draw whatever you please,” he says.

Manjul has also written opinion pieces, but only when he is unable to convey the depth of his feeling in cartoons, like after Mario Miranda died. “Also, I wrote a piece when I visited Jaitapur. If I don’t draw a cartoon, I become uneasy. But I regret not travelling more in India, not knowing a lot of things. Right now, this is too exciting for me, so I am not going to take a vacation till 2015,” he grins.