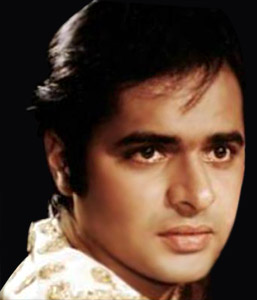

Actor Farooque Sheikh speaks on the malaise of money dictating quality in our cinema, when dedication and passion actually should.

by Humra Quraishi

Farooque Sheikh was the eternal reel sweetheart, the man with more than good looks and a formidable acting talent. He did few films, but made an impact with each one, before moving on to do theatre and television and making a mark there as well.

Farooque Sheikh was the eternal reel sweetheart, the man with more than good looks and a formidable acting talent. He did few films, but made an impact with each one, before moving on to do theatre and television and making a mark there as well.

For somebody who seems to be so soft-spoken on screen, Farooque Sheikh in the flesh comes as a bit of a surprise. He minces no words, spares nobody in his criticism. Recently, he took up the cudgels against the Tamil Nadu Government in favour of Kamal Haasan’s Vishwaroopam, which the Government banned from release despite certification from the Censor Board. “Of what use is the Censor Board if the Government is going to Talibanise films and filmmakers in this fashion?” Sheikh had famously thundered on TV.

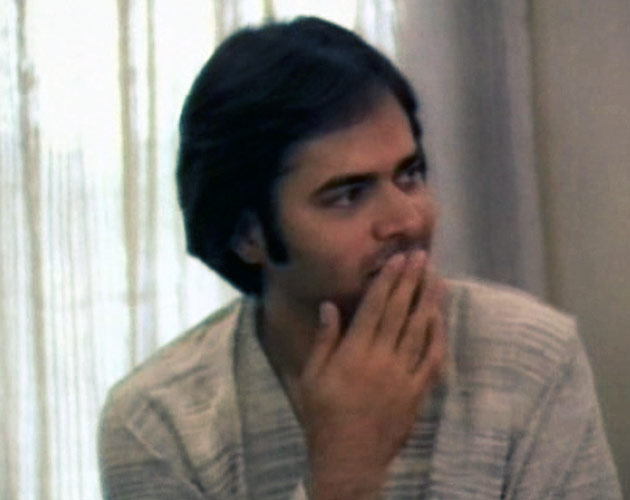

I met and interviewed the actor twice, once in the 1990s and then in 2005 when he was speaking at a seminar here in New Delhi. He’d been his usual outspoken self and did not hedge around questions. It is refreshing to find film personalities like him who are not much bothered about political correctness.

Sheikh had a lot to say about the Hindi film industry, and how hypocritical and money-crazy the current generation of filmmakers are.

“Successful filmmakers in Bollywood today have big budgets, but no sensibility or sensitivity. Cinema has become totally commercial, a  commodity to be sold,” he said. “There are no film producers today like K Asif and Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy, or even Mehboob sahib. Mehboob sahib had no money, yet his passion drove him to make films. Bimal Roy lived in a rented accomodation all his life. It took MS Sathyu a full 20 years to repay the loan he took to make Garam Hawa. That level of commitment is missing in today’s film producers. Today, film producers simply go by whether the film will be a box office hit. Maybe because there are too many business interests involved.”

commodity to be sold,” he said. “There are no film producers today like K Asif and Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy, or even Mehboob sahib. Mehboob sahib had no money, yet his passion drove him to make films. Bimal Roy lived in a rented accomodation all his life. It took MS Sathyu a full 20 years to repay the loan he took to make Garam Hawa. That level of commitment is missing in today’s film producers. Today, film producers simply go by whether the film will be a box office hit. Maybe because there are too many business interests involved.”

We soon began chatting about stereotyping of communities in Indian cinema. He became quite animated on this subject. “Community perceptions in our films have always been about stereotypes. The Christian girl is a girl dancing or wearing short skirts with signs that she is a ‘fast’ girl. The Parsi is always shown as blundering. The Sikh is either a soldier or a man constantly eating parathas; nobody on screen shows him like Manmohan Singh.

“In the case of Muslims, the characters are hardly believable. Why do they portray the Muslim man always in a lungi and a vest? Or he is a gaddaar. As a token, one of them will be very patriotic so that the entire community is not misunderstood. The other stereotypes, with 300 aadabs in one film and women wearing ghararas or cooking kormas, are also absent in real life Muslim households.”

He added that since cinema was popularly perceived to be an entertainment medium, so whatever was shown on the big screen was automatically assumed to be something that need not be taken seriously. “So nobody complains about these stereotypes.” He was also quick to point out that television does have a bigger impact on people’s lives than cinema, and that things shown on TV have sometimes been life-changing in villages.

He added that since cinema was popularly perceived to be an entertainment medium, so whatever was shown on the big screen was automatically assumed to be something that need not be taken seriously. “So nobody complains about these stereotypes.” He was also quick to point out that television does have a bigger impact on people’s lives than cinema, and that things shown on TV have sometimes been life-changing in villages.

Who, in his opinion, held out some hope as a filmmaker? “Anand Patwardhan,” he replied. “He has fought the system. And fighting the system is not an easy task.”

Watch a trailer of the charming Chashme Buddoor starring Farooque Shaikh and Deepti Naval:

(Pictures courtesy movies.ndtv.com, www.indianetzone.com, www.santabanta.com, www.thehindu.com)