Most of us identify Gemini Ganesan as film star Rekha’s father. However, there was more to the superstar than cinema.

by Humra Quraishi

I chanced upon a book, Eternal Romantic: My Father, Gemini Ganesan, by journalist and writer Narayani Ganesh, a few years ago. The book is about the halo around the Tamil superstar, the lesser-known things about him, and most importantly, it captures him in the context of the times he lived in, the Tamil Nadu of his birth and work, and everything else in between.

As per the book, Gemini Ganesan spent his formative years in the royal principality of Padukottai in Tamil Nadu, followed by a year in the Ramakrishna Mission Home in Chennai, where he learnt yoga and attended Vedanta classes. This was followed by his years at the Madras Christian College, and much later, with a glorious career in cinema.

As per the book, Gemini Ganesan spent his formative years in the royal principality of Padukottai in Tamil Nadu, followed by a year in the Ramakrishna Mission Home in Chennai, where he learnt yoga and attended Vedanta classes. This was followed by his years at the Madras Christian College, and much later, with a glorious career in cinema.

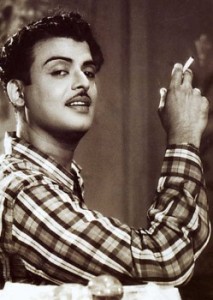

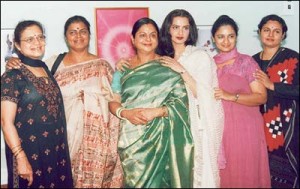

Written with a great deal of transparency, the book dispels the mystique around Gemini Ganesan, making him out to be normal family-oriented man who was not at all filmi. From the several pictures of him and his family in the book, he appears to be a traditional family man, surrounded by his large family in an old-world setting.

Frank and devoted

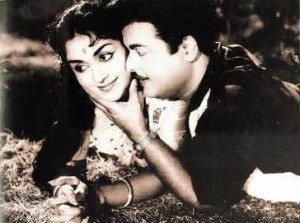

He was known for being far ahead of his times, both in his work and personal life. He was candid about his relationships with his co-stars, and did not ever deny the existence of film stars Pushpavalli and Savithri in his life. He married them, fathered their children. Amazingly, his first wife, TR Alamelu, popularly called Bobjima, appeared to be utterly comfortable with the Gemini-Pushpavalli-Savithri situation, and also their children. Even more surprisingly, all of his children, with all three women, got along well with their half-brothers and sisters. One of these children was Rekha, who would later become a superstar in Hindi films.

The more I read, the more I pondered on Bobjima and the courage with which she faced her husband’s relationships. She seems to have been a woman completely in love with her husband, and she was with him right till the end. If a film was to be made on the life of Gemini Ganesan, Bobjima would definitely play the heroine in an extraordinary relationship that endured till the end.

Narayani was born to Bobjima. She writes, “When I think of appa, the words that spring to mind are charming, handsome, affectionate, witty, responsible and compassionate. He was  an interesting person…because his interests went far beyond cinema. As a dashing romantic actor, appa did have relationships outside his marriage, but his relationship with us remained the same. He was the same caring father, son and nephew, but of course, I would not be able to say what went through my mother’s mind. Because children were not part of their private discussions (if they had any) and my grandmothers were so benign and full of love – for appa and for all of us, so there was no question of ugly fights or hurling of accusations and that sort of thing.

an interesting person…because his interests went far beyond cinema. As a dashing romantic actor, appa did have relationships outside his marriage, but his relationship with us remained the same. He was the same caring father, son and nephew, but of course, I would not be able to say what went through my mother’s mind. Because children were not part of their private discussions (if they had any) and my grandmothers were so benign and full of love – for appa and for all of us, so there was no question of ugly fights or hurling of accusations and that sort of thing.

“I would say that we all had a great deal of respect for him and for each other. As an actor, appa’s USP was that he had a way with women; he oozed charm and with his candy-box good looks, wide-eyed innocence and gentle ways, he won over the hearts of more than a generation of fans. For them, he was the eternal romantic hero…”

About Rekha

Narayani writes about Gemini Ganesan with touching honesty, leaving out nothing. “At Presentation Convent, Madras, where I studied, a girl struck up a conversation with me after school one day. I must have been nine or ten years old.

‘Why do you and your sister go home in different cars?’ she asked. I was puzzled. My two older sisters had finished school. My younger sister was still a baby. ‘Come, I will take you to her,’ the girl said, taking me by the hand. I met Rekha for the first time. She was pretty and her eyes were lined with mascara. She said her name was Bhanurekha. ‘What is your father’s name?’ I asked.

‘Why do you and your sister go home in different cars?’ she asked. I was puzzled. My two older sisters had finished school. My younger sister was still a baby. ‘Come, I will take you to her,’ the girl said, taking me by the hand. I met Rekha for the first time. She was pretty and her eyes were lined with mascara. She said her name was Bhanurekha. ‘What is your father’s name?’ I asked.

‘Gemini Ganesan,’ came the reply. My eyes filled with tears. How can that be? He was my father. When Chinamma came to take me home, I blurted out the story. ‘Never mind,’ she said.

“Another day, I pointed out Rekha to Chinamma and she said, ‘She is like your sister. And she’s pretty.’ Then there was Rekha’s younger sister, Radha, who was even prettier, I thought. Her resemblance to appa was startling. When I was a little older, I learnt that they were born to Pushpavalli and appa, and that they lived with their mother and other siblings, too…”

Other interesting details about Gemini Ganesan the father were that he was very particular about his children’s teeth and their upkeep. “One of the earliest memories I have of my father is of him asking me to show him my teeth. He would inspect them regularly, and horrified that my two upper front teeth were parting ways, leading to an A-shaped passage behind, he whisked me off to the dentist!”

Actor Kamal Haasan, who’d worked with him as a child actor in his movies, mentions in the books’s foreword, “Gemini mama (uncle) was larger than  life; there was so much more to him than his screen persona. That was what was so exciting – cinema was not his entire life, it was a vocation, a profession he chose over others. ‘To me, life is oxygen, not cinema!’ he would say. If he hadn’t been an actor, he might have retired as an academic, with teaching stints in, who knows, Pudukkottai, Chennai, Delhi, UK, USA. He let his laurels rest lightly on his shoulders – to him, success was neither a crowning glory nor a heavy cross. And at a time when celebrities made it a point to publicise their acts of charity, he did it quietly, without fuss…

life; there was so much more to him than his screen persona. That was what was so exciting – cinema was not his entire life, it was a vocation, a profession he chose over others. ‘To me, life is oxygen, not cinema!’ he would say. If he hadn’t been an actor, he might have retired as an academic, with teaching stints in, who knows, Pudukkottai, Chennai, Delhi, UK, USA. He let his laurels rest lightly on his shoulders – to him, success was neither a crowning glory nor a heavy cross. And at a time when celebrities made it a point to publicise their acts of charity, he did it quietly, without fuss…

‘I touched and felt film ‘stars’ for the first time in my life when I was three-and-a-half years old. The stars were Gemini Ganesan and Savithri, and I was to play their son in the film Kalathur Kannamma. Till then, I had no idea that actors were flesh and blood humans – I cannot forget the experience as they held me close in their arms, their ‘child’. I began addressing them as amma and appa on and off the sets. I’m told I had to be ‘weaned’ away from my screen parents!’

(Pictures courtesy www.veethi.com, ibnlive.in.com, thehindu.com, www.mid-day.com, rediff.com, www.masala.com)