Most children experience several cultures growing up in different countries. Mumbaikars, however, develop a culture that is uniquely their own.

by Shweyta Mudgal

by Shweyta Mudgal

I was born in Mumbai, where I was raised until my early 20s. At 23, I moved to Los Angeles and at 24 to New York City. Ten years later, I now live in Singapore and call three cities my home – Mumbai, New York and Singapore, all at the same time – in descending order of the time I’ve spent living there.

By Fall this year, I will have moved out of Singapore back to Mumbai for another year or so, after which it will be time to return to NYC once again. As I write today, this is what the nomadic pattern of my life in the near future looks like.

There are no guarantees, however. Having been bitten by this ‘multiple homes’ bug, there may just be some diversions en route, should other cities offer interesting work/ life opportunities midway through this globe-trot itinerary and lure us (daughter, husband and I) to their shores.

The above path of my life thus far has brought me in direct contact, on a day-to-day basis, with three different cultures –

- The First Culture (The Indian Culture): the one that I was born and raised in and will permanently seek allegiance to.

- The Second Culture (The American Culture): the one that I believe I really grew up and found my true self in. Also the one where my daughter will permanently seek her allegiance.

- The Third Culture (The Asian Culture): the one where we (daughter, husband and I) presently live.

Yet, I am not who you would call a pure TCK – a Third Culture Kid. For, according to its formal, sociological and anthropological description, “A third culture kid is a person who has spent a significant part of his or her developmental years outside their parents’ culture.” Since I moved out of my so-called ‘parents culture’ only after I turned 18, I am just another adult who’s lived in a few countries. My toddler, on the other hand, in her small span of life (of 21 months), is considered a TCK, who embarked on the third culture bandwagon as soon as she turned one. By the time she turns three, she would have lived in at least three different countries. Born an American, to Indian parents, she currently lives in Singapore. Plainly put, she flew before she walked.

Sociologist Ruth Hill Useem coined the term ‘Third Culture Kids’ in the early fifties. And interestingly, as I found through my research, the term was coined in India! It was here, after spending a year on two separate occasions with her three children, that the term was born. Initially the term ‘third culture’ referred to the process of learning how to relate to another culture. In time though, it started referring to children who accompany their parents into a different culture as Third Culture Kids” or TCKs. Useem used this term because TCKs integrate aspects of their birth culture (the first culture) and the host culture (the second culture), creating a unique ‘third culture’, i.e their own shared way of life with others also living outside their passport cultures (the land they hold passports of).

Sociologist Ruth Hill Useem coined the term ‘Third Culture Kids’ in the early fifties. And interestingly, as I found through my research, the term was coined in India! It was here, after spending a year on two separate occasions with her three children, that the term was born. Initially the term ‘third culture’ referred to the process of learning how to relate to another culture. In time though, it started referring to children who accompany their parents into a different culture as Third Culture Kids” or TCKs. Useem used this term because TCKs integrate aspects of their birth culture (the first culture) and the host culture (the second culture), creating a unique ‘third culture’, i.e their own shared way of life with others also living outside their passport cultures (the land they hold passports of).

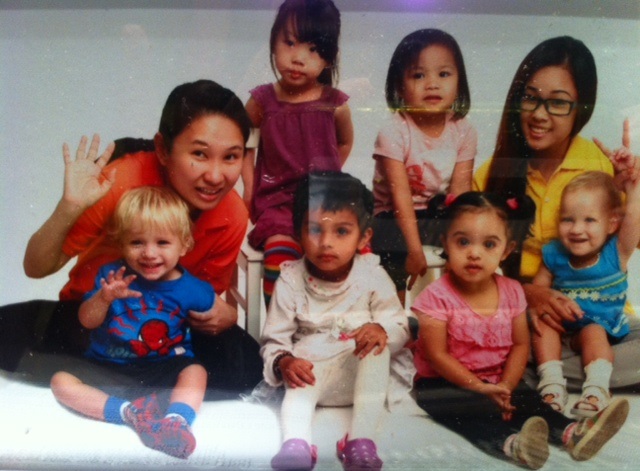

On a global note, TCKs naturally have plenty of positive attributes such as multilingualism and an objective outlook, and they are used to an intercultural lifestyle. Moving from country to country is routine for them and is usually accomplished with ease. They grow up within a globalised culture, marked by well-travelled parents and friends, international schools and vast future opportunities. They easily build relationships with all cultures, while not having full ownership of any. Elements from each culture they encounter get assimilated into their life experiences, making them well rounded, global citizens of the future.

There are flipsides to being a TCK, too. Sometimes, children that have lived in multiple countries through their growing years, lack a sense of home. While they absorb various cultures to make up their own ‘third culture’ they often miss an anchor-culture; something that they can root themselves to. Some kids that have been away from their ‘passport cultures’ for long, end up as cases where their passport belongs to a place that they can no longer relate or belong to. On repatriation, they suffer from a ‘reverse culture shock’ and/ or identity crisis and often pine to return to their adopted country.

Yet, the pros outnumber the cons in most cases. More often than not, TCKs have been found to be smarter, outspoken, more sociable, open, humorous, sensitive, non-discriminative and tolerant of other cultures, overall. They usually develop strong observation powers and cross cultural skills par excellence, due to constant immersion in newer surroundings that take them out of their comfort zones. They have been called ‘the prototype citizens of the future’, which directly translates to the thought that a childhood lived among many cultures would one day be the norm rather than the exception.

But so far, social scientists have conducted the TCK discussion only at a global level – in the macroscopic scheme of things. Try applying that theory on a microscopic level, to local cultures and our very own Mumbai, with its cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic, ‘melting pot’-like credentials, offers itself up as a perfect example, breeding millions of local TCKs within!

As is common knowledge, Mumbai is a city of migrants. Its original inhabitants are the Kolis – the fishing community. Post-independence, the Parsis, Bhatias, Pathare Prabhus, East  Indians and Muslims moved in. Most of Mumbai’s local Marathi community was formed by migrant workers from within Maharashtra, who came here to work in the textile mills. South Indians with their professional educational qualifications, flocked to the city, during the 60s and 70s, in search of white-collared jobs as clerks and typists. Some South Indian hoteliers such as the Shettys set up their Udipi joints here. Migrants from North India moved to the city to work as dhobis, newspaper vendors, milk suppliers and carpenters, while construction workers and banias came from the nearby states of Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Indians and Muslims moved in. Most of Mumbai’s local Marathi community was formed by migrant workers from within Maharashtra, who came here to work in the textile mills. South Indians with their professional educational qualifications, flocked to the city, during the 60s and 70s, in search of white-collared jobs as clerks and typists. Some South Indian hoteliers such as the Shettys set up their Udipi joints here. Migrants from North India moved to the city to work as dhobis, newspaper vendors, milk suppliers and carpenters, while construction workers and banias came from the nearby states of Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Naturally as a result of this intra-national influx, a lot of the city’s children can be considered as local TCKs, albeit only at a more geographical, contextual level that lies within the nation’s boundaries. Growing up in Mumbai, it is not uncommon to find kids of Tamilian parents speak better Marathi, Hindi and English than Tamil. Or families in which the grandparents hail from Pakistan, the parents grew up in Punjab and the kids are growing up in Mumbai.

With India’s intra-ethnic society increasingly opening up, one can find several inter-caste marriages that result in diversely brought up children, who are exposed to multiple cultures from various parts of the country, passed on to them by their parents, while subsconsciously already being immersed in the third culture – the inherent culture of the city. In Mumbai, as is evident one need not hail from a ‘Gujju’ household to be a good garba dancer or a ‘Punju’ background to be excellent at bhangra. Communal celebrations of iconic festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi, Navratri, Holi, Janmashtami and Christmas have shown over time the city’s cosmopolitan spirit in its inclusive participation; members of all religious faiths come together to celebrate these, irrespective of their individual cultures.

A child born in Mumbai, might start off being a member of a clique such as Hindi, Sindhi, Marathi, Punjabi, Gujarati, Bihari, Tamil, Kannadiga, Malyali, Muslim, Parsi, Sikh, Christian, Jew and what not, based on their parents’ culture, yet by the time he/she has grown up, they would have had plenty of opportunity to modify and adapt this tag to create their own unique micro identity – of being a Mumbaikar. That identity, as one often finds these days, trumps over any specific regional affiliations, encompassing all diversity within its realm and instills a sense of belonging to the city/country as against a religion/faith. Sports such as cricket, with the introduction of the IPL, have helped segregate the large country on a geographic urban divide, fostering the emergence of newer identities that one seeks allegiance to – in this case, cities such as ‘Mumbai’ v/s ‘Delhi’.

When I was growing up in Mumbai, I was often asked the crude and grammatically confusing ‘What are you?’ question. No, not the kinds that would entail a pat ‘Umm…Can’t you see? I am a girl’ kind of an answer. But more like the kinds that warranted a ‘I am Gujarati/Marathi…’ type response. Being ‘Hindi-speaking’, that too from India’s centrally located state, Madhya Pradesh, didn’t help much. Adding to the confusion were my fluency in Marathi and looks that matched the Tamil best friend’s. Hence often my reply would be – “I am Hindi. My parents hail from MP but I am born and brought up in Mumbai.”

I went to a convent school and like many other kids growing up then, had Hindu, Muslim, Parsi, Sikh, Anglo-Indian and Jewish classmates. I had no idea then that I was developing my own sub-culture – each time I crossed my right hand over my head, chest and shoulders saying ‘In the name of the father, the son, the holy spirit…Amen’ while I stood in a Hindu temple before a Ganesh idol. Or the other time, when I decided to join my Muslim friend in fasting for a day, for a God who didn’t exist in my home. To me it was an innocent, fun way to join my friend in doing what he did. And of course there was the lure of the yummy goodies that would be served in the evening to break the fast with.

Both these ‘third culture’ acts were not of my parents’ culture – which was inherently ‘Hindu’. These were my own unique cultural adaptations, where I was integrating acts from my first culture (of being a Hindu) – of going to a temple or starving myself in the name of God and acts from my second culture (of the city) – of a Christian method of prayer or a Muslim religious Iftaar ceremony, to make my own unique third culture! It was a juxtaposition of cultures that I had happily accepted and made my own. In that sense, I and all those other kids who grew up like me, in multi-cultural Mumbai, are local Third Culture Kids.

That kind of upbringing perhaps created in me a fascination for the idea of living a multi-cultured life, not only on the microscopic but also the macroscopic level. And today, as things go, thanks to our current global mobility opportunity, I’ve been fortunate to pass it on, by raising a Third Culture Kid of my own.

I like the idea of having my toddler spend the early years of her life establishing and then breaking her own comfort zone while being a ‘cultural sponge’ and integrating elements of various cultures in her personality. I hope some day she counters the question, “Where are you from?” with yet another question, “Well, where should I start? I was born in…”

I like the idea of having my toddler spend the early years of her life establishing and then breaking her own comfort zone while being a ‘cultural sponge’ and integrating elements of various cultures in her personality. I hope some day she counters the question, “Where are you from?” with yet another question, “Well, where should I start? I was born in…”

I’d like to see her growing up with the feeling that she belongs everywhere and yet nowhere in specific. That she is of the world and the world is her oyster. That she is able to experience it all and pick and choose what most resonates with her, to take that with her wherever she goes. That even though she will be raised a Third Culture Kid, she will have more than just three cultures to belong to. And hopefully soon, she will be joined my many more kids like her, who will know what it is like to have the best of both worlds…even if they don’t have just one that they can call their own, fully.

The adage ‘Home is where the heart is’ has never been truer and more literal than it is now. Today, it means that we carry our home(s) in our heart, wherever we go. And thankfully for multicultural/multi-home dwellers like us, there’s no baggage restriction on the number of homes that the heart can carry!

A Mumbaikar by birth and a New Yorker by choice, recently-turned global nomad Shweyta Mudgal is currently based out of Singapore. An airport designer by day, she moonlights as a writer. ‘Outside In’ is a weekly series of expat diaries, reflecting her perspective of life and travel, from the outside-in. She blogs at www.shweyta.blogspot.com and is happy that no one asks her “What are you?” in Mumbai anymore!

(Pictures courtesy Shweyta Mudgal, clastcloudchurch.org, gulfnews.com)