‘Language purist’ Shweyta Mudgal wants everybody to speak and write perfect English, and guess what? The Singapore Government agrees, too.

I cannot stand inaccuracy in language. I am a proponent of linguistic purity, grammar, punctuation and spelling. More often than not, I’ve been a flawless speller. In ‘Dictation’ class (when the teacher would dictate 20 random words in English that we would have to write down in our books), I recollect receiving an eternal 100 per cent score. Having been an extremely confident English linguist ever since I can remember; I rarely ever use the ‘spell-check’ mode when I type, easily switching between ‘American’ and ‘British’ spellings, as need be. Punctuations have always mattered to me. They are as important as the content of my writing. A well-written, correctly spelt and punctuated piece of prose or poetry gives me a high like none other.

I cannot stand inaccuracy in language. I am a proponent of linguistic purity, grammar, punctuation and spelling. More often than not, I’ve been a flawless speller. In ‘Dictation’ class (when the teacher would dictate 20 random words in English that we would have to write down in our books), I recollect receiving an eternal 100 per cent score. Having been an extremely confident English linguist ever since I can remember; I rarely ever use the ‘spell-check’ mode when I type, easily switching between ‘American’ and ‘British’ spellings, as need be. Punctuations have always mattered to me. They are as important as the content of my writing. A well-written, correctly spelt and punctuated piece of prose or poetry gives me a high like none other.

Attending a Roman Catholic Convent School where English purism was held as high in priority as prayer may have had a lot to do with my proficiency and passion for languages in general. Here, English was our first language while Hindi and Marathi were the second and third languages respectively. Students were highly encouraged to use Hindi and Marathi only in those respective classes, while using English as the prime conversational medium at all other times, within the school premises.

At home, I was brought up by a Hindi teacher, who I called Mom. So fluency alone in that language would not help; proficiency had to be achieved. And growing up in a largely Marathi-speaking society assured that I was a good Maharashtrian as well – as far as reading, writing and speaking in Marathi was concerned. My linguistic regret manifests itself in my inexpertise in French – a language I studied for a couple of years only. On account of this short duration of study and limited verbal interaction with other French speakers, I did not go as far with it, as much as I would have loved to.

Being this particular about my language skills over the years, I have had to try and develop an increased sense of patience within myself – to resist the inherent urge to correct other people’s spelling, grammar and pronunciation, especially in English.  The Urban Dictionary politely refers to people like me as ‘Language Purists’, while the Urban majority calls us ‘Language Nazis’. My Mom who keeps me honest at all times, simply prefers the term ‘Angrez ki aulaad’ (Child of an Englishman) adding the adage, “Angrez chaley gaye, inko chhod gaye” (The British left the country, but left this one behind).

The Urban Dictionary politely refers to people like me as ‘Language Purists’, while the Urban majority calls us ‘Language Nazis’. My Mom who keeps me honest at all times, simply prefers the term ‘Angrez ki aulaad’ (Child of an Englishman) adding the adage, “Angrez chaley gaye, inko chhod gaye” (The British left the country, but left this one behind).

Clearly, as you can already tell, she is the individual most often corrected by me.

So to say I was flabbergasted and completely taken by surprise when I landed here in Singapore to hear an entire nation speak wrong English, is not an exaggeration. It’s called Singlish, I am told. Put succinctly, it is a Singaporean brand of spoken English; basically English with Chinese grammar and spoken with a distinctive Singaporean and/or Malaysian accent.

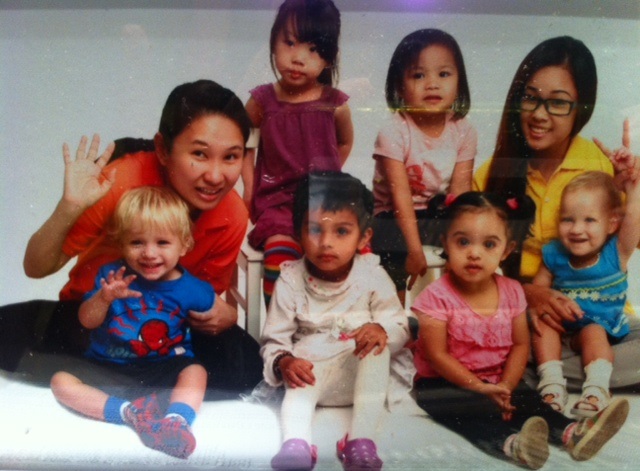

According to a BBC news article, “Singlish is the product of Singapore’s history as a melting pot of cultures, combining the influence of an English-speaking colonial master and a firmly multiracial society. The result is an English-based vernacular, spiced up with terms from Hokkien, Malay, Tamil and whatever other language happens to come along.”

As though that is not mind-boggling enough, Singlish is spoken at supersonic speed, with words pronounced so abruptly and cut short at times, that one is usually left with a “Sorry?” and if exasperated like me, a rather impolite “What?” at the receiving end.

Don’t get me wrong. My problem is not that English takes on its own version here. I am all for that contextual adaptation, being a casual Hinglish (a portmanteau of Hindi and English) user myself from time to time. My problem arises when the grammar goes wrong. That is just, plainly put, blasphemy for my ears and eyes even. This sacrilege carries on in print as well, gradually making me reach my tipping point.

Yet having said that, I do see how the Singaporean strategy of shortening sentences into simple words does the job for them. Singapore’s premier foodie site is called http://www.hungrygowhere.com/. With a name like that, one clearly knows where to go, when hungry.

An eye surgery ad printed in local media reads as follows – “Advantage of EPI-Lasik: Preserve more cornea tissue; suitable for those involve in contact or aggressive media”. This ad is in Singlish, which horrifies a newbie like me, who wants to grab hold of the nearest pen and make prompt corrections. Singlish, in print, avoids complex phrases, verbs and definite articles, tenses, voices and even pluralities and gender in some cases. Yet albeit grammatically incorrect, it puts across the point.

Locals abbreviatedly reply to my queries in a “Can can” or a “Cannot”, saving their and my time in the process, by sparing the use of the entire sentence that goes along with that. Yet, they won’t forget to put an additional “Lah” to emphasise the point being made or an ‘already’ (pronounced as “oreddy”) at the end of a sentence, to indicate that the act should already have taken place.

The maid often asks, “So how?” in response to any instruction given to her. That’s when the epiphany of this intelligently-surmised question hit me! This two-worded question yields the power to get me rallying off, with all the details of the job, the what, when, where and how of it all. So yes, the cut-short strategy that Singlish applies works, as does its utilisation of an assemblage of words from various languages.

But it is its impurification of grammar that really drives me up the wall. And sitting atop that wall, to my utter amusement, whom do I find? None other but the Singaporean government – which, equally upset with this grammatical inappropriateness, launched a national movement – the ‘Speak Good English Movement’ (http://www.goodenglish.org.sg/) in April 2000. This campaign encourages Singaporeans to speak grammatically correct English that is universally understood, through a wide range of workshops, seminars, contests and programmes all year round.

Call me biased, but Hinglish does not feel as wrong somehow. At least we do not change the tense of English words. We may shorten them such as ‘vocab’ for vocabulary, ‘funda’ for fundamental and ‘fab’ for fabulous. Yet, most of the times, we just swap out an English word for its Hindi equivalent, thereby exporting new words in the existing lexicon of the English language – words such as ‘badmaash‘, ‘timepass’, ‘prepone’ and my personal favourite, ‘Bangalored’, among many others. At times we’ve even gone all out and taught the Brits their ubiquitous “innit” sounds better in the British Asian speech as “hai na” – a Hindi tag phrase, stuck on the ends of sentences and meaning “isn’t it?”

Call me biased, but Hinglish does not feel as wrong somehow. At least we do not change the tense of English words. We may shorten them such as ‘vocab’ for vocabulary, ‘funda’ for fundamental and ‘fab’ for fabulous. Yet, most of the times, we just swap out an English word for its Hindi equivalent, thereby exporting new words in the existing lexicon of the English language – words such as ‘badmaash‘, ‘timepass’, ‘prepone’ and my personal favourite, ‘Bangalored’, among many others. At times we’ve even gone all out and taught the Brits their ubiquitous “innit” sounds better in the British Asian speech as “hai na” – a Hindi tag phrase, stuck on the ends of sentences and meaning “isn’t it?”

The ‘pick and mix’ approach that Hinglish and to a certain extent Singlish adapt, is worth embracing. Language has essentially evolved over the years and continues to do so. It is natural and inevitable that it will adapt and change to whatever is around. It often doubles up as not just a verbal means of communication, but as a representational tool of our identity as well. And just as all of us step in and out of multiple identities every day, so does our language and its vocabulary. It has facets of similarity that sometimes help us identify with the alien culture to feel at home with it, such as when my Singaporean Chinese taxi driver exclaims “Aiyyoh!” at missing a turn. Or when a little British boy runs off, offended, saying “Katti” to his other friends in the play area.

Imbibing the local language’s nuances and pronunciations within one’s vocabulary can help one immerse easily within an alien culture; to blend in, to understand and be understood. Doing all this without wrecking its grammatical, punctuation and spelling sanctity is perhaps difficult, even unrealistic at times, but still plausible. Because a Singapore Sling is not the same as a Singapore Slang.

And commas save lives; for instance – Let’s eat Baby. Let’s eat, Baby!

A Mumbaikar by birth and a New Yorker by choice, recently-turned global nomad Shweyta Mudgal is currently based out of Singapore. An airport designer by day, she moonlights as a writer. ‘Outside In’ is a weekly series of expat diaries, reflecting her perspective of life and travel, from the outside-in. She blogs at www.shweyta.blogspot.com and avoids Singaporean Slang. The Singaporean Sling though, is a different story altogether (hic)!

(Pictures courtesy photobucket.com, ideasevolved.com, indianfunnypicture.com, jainismus.hubpages.com)