Nihit Bhave attended a screenwriters’ conference held in Mumbai, which had the biggies in Indian cinema share their writing secrets.

If you’re a writer, you know the ‘blank document’ syndrome, otherwise known as the blinking-cursor-is-judging-you syndrome. It is the awkward pause between opening a document and writing its first word (I would have said ‘pregnant’ pause, but a writer never feels more impotent than at that stage, so I shall refrain from adding salt to the wound). It was certainly a big relief to know that this impairment hasn’t spared the best of the best.

“As a writer, my biggest challenge is a blank document,” said Juhi Chaturvedi, who wrote the film Vicky Donor.

Thankfully, the recently concluded event, ‘The 3rd Indian Screenwriters Conference – Untold Stories: Screenwriting And Truths Of Our Times’ was able to throw up many remedial suggestions for such syndromes, and also went on to shed light on some of the most pressing issues today’s young writers are facing.

Unfortunately, due to my own ignorance and complacency, I missed the first day and apparently a brilliant key-note speech. But going by Day 2 and Day 3, I can safely say that Act I must have been totally worth it.

Day 2 was primarily about the upcoming talent and the hurdles they face taking their stories from paper to producer, and from producer to the parda of cinema. The first session of the day, ‘The charge of the new ‘write’ brigage’ included panelists like Juhi Chaturvedi (Vicky Donor), Sanjay K Patil (National Award winning Marathi film Jogwa), Reema Kagti (Talaash, ZNMD, Honeymoon Travels, etc), Habib Faisal (Ishaqzaade, Band Baaja Baaraat, Do Dooni Char) and Akshat Verma (Delhi Belly) and was moderated by Pubali Chaudhari (Rock On!!, Kai Po Che). The insights from this session were unparalleled. From a coy Habib Faisal to an outspoken Akshat Verma, and from a commercially successful Reema Kagti to a relatively underrated Sanjay Patil, the writers put forth their points about creativity, content, contemporary challenges and personal hurdles for writers.

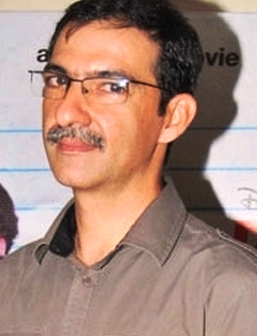

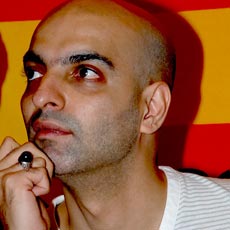

“I’ve never set out to write earth-shattering cinema. In fact, I’ve never done anything original. I’ve done clichés with my own twists and gotten away with it!”, Habib Faisal (in pic on left) said.

“I’ve never set out to write earth-shattering cinema. In fact, I’ve never done anything original. I’ve done clichés with my own twists and gotten away with it!”, Habib Faisal (in pic on left) said.

Speaking about the very unusual storyline for Honeymoon Travels, the film’s writer and director Reema Kagti said, “When I was writing Honeymoon Travels…it was the story of a pitch-perfect couple who then turns out to be a superhero couple, but since no Indian producer would let me make a feature film on it, I added six other short stories and juxtaposed this one with those!”

Other memorable quotes during this session came from Sanjay Patil, who spoke of his Marathi film Jogwa thus: “My film Jogwa was lying with me for 12 years because throughout the film, both the heroine and the hero were in sarees.” Juhi added, “Nothing scares producers like a writer who can’t categorise his own work. I did not know whether Vicky Donor was a rom-com or a social message film, so I said ‘drama’ and that threw people off.”

The second session, and the most entertaining one at that, was ‘Is the old order cracking?’, where moderator Govind Nihalani (Ardha Satya, Dev, Thakshak) quizzed panelists Urmi Juvekar (Oye Lucky…, Shanghai), Sanjay Patil, Bejoy Nambiar (David, Shaitaan), Rakeysh Mehra (Rang De Basanti, Delhi 6) and Abbas Tyrewala (Jaane Tu…Ya Jaane Na, Maqbool, Main Hoon Na) about the age-old three-act structure of screenwriting, linear and non-linear narratives and challenges writers face with them.

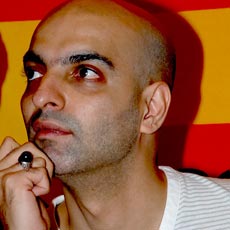

Abbas Tyrewala (in pic on right) was a revelation in this session. His explanation of a ‘structure’ for writing films was incredibly clear. “Imagine  this. A smoker feels the need to smoke because he ‘imagines’ that his mind and body are lacking something. After a cigarette, a sort of ‘high’ replenishes this missing element and the person reaches the same level of normalcy (that a non-smoker is always at!) Similarly, when a viewer walks into a theatre, they’re at a level of normalcy. Your story has to create a trough and a consecutive crest – a conflict and a resolution – but with the effect of a (cinematic) high that will ensure that the viewer exits the theatre at the same normalcy level, but with an enhanced experience.”

this. A smoker feels the need to smoke because he ‘imagines’ that his mind and body are lacking something. After a cigarette, a sort of ‘high’ replenishes this missing element and the person reaches the same level of normalcy (that a non-smoker is always at!) Similarly, when a viewer walks into a theatre, they’re at a level of normalcy. Your story has to create a trough and a consecutive crest – a conflict and a resolution – but with the effect of a (cinematic) high that will ensure that the viewer exits the theatre at the same normalcy level, but with an enhanced experience.”

It was interesting to see the linear v/s non-linear narrative debate between these young writers and Javed Akhtar, who nonchalantly took them on from his seat in the audience.

After two more sessions on TV content and the (hypothetical) revolution that’s in store for us on the small screen, the evening was concluded by a ceremony awarding special FWA honors to Gulzar and Salim-Javed. The awards were presented by Hema Malini.

Day 3 forced writers to face their fears and talk about what they hated the most – numbers, contracts, statistics, constitutional acts, royalties, infringements, arbitrations, etc. So after a brief morning session, ‘The empty playroom: why such few children’s films?’, led by Gulzar and Nila Madhab Panda (I Am Kalam) amongst others, we proceeded to the dark side and shed light on the things that also matter.

This day also proved fruitful, as the people at Film Writers’ Association managed to string together lawyers, Producers’ Guild representatives and writers on the same stage to discuss minimum basic contracts for writers, copyright issues and the implication of the amendments to the Copyright Act 1957.

FWA also celebrated the work of the father of Indian TV, late Manohar Shyam Joshi, who created mega TV serials Hum Log and Buniyaad.

Just to be in the same room as Gulzar and Javed Akhtar, Rakeysh Mehra, Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti and listening to them talk about screenwriting, made attending the event worth it. There was surely a lot to learn and understand. Because unlike what we’d like to believe, screenwriting is much more complicated than putting pen to paper, words to a story and a climax to a beginning.

Nihit Bhave is a film journalist based in Mumbai.

(Pictures courtesy piquenewsmagazine.com, firstpost.com, c2ctara.com))