Former journalist, now writer and archaeology student Shubha Khandekar talks about creating archaeological cartoons and studying history with a sense of humour.

by The Editors | editor@themetrognome.in

Let’s face it – we Indians are a ‘sensitive’ lot. Increasingly, everything hurts our feelings; unintended slights, a jokey reference to our history and culture, even a stray illustration about something Indian. But Shubha Khandekar loves taking a fond, humorous look at our history through cartoons – the former journalist and now writer and PR professional has been a dedicated archaeology student for the longest time, and wonders why we “can’t stick out our tongue at Kautilya, pull Anathapindika’s leg, make fun of the globe-trotting Aryans and the seafaring Harappans?”

In an interview, the 50-something Kalyan resident tells The Metrognome about being one of the few Indians drawing archaeological cartoons, how our apathy and callousness towards our archaeological wealth, why she wants a device that can see underground, and what those wishing to study archaeology should do.

When did you first develop an interest in archaeology?

I postgraduated in Ancient Indian History at Delhi University, after which archaeology was merely the next logical step forward. I did a one year PG diploma in archaeology from the School of Archaeology, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi, after which I went to the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute in Pune for a Ph.D.

I postgraduated in Ancient Indian History at Delhi University, after which archaeology was merely the next logical step forward. I did a one year PG diploma in archaeology from the School of Archaeology, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi, after which I went to the Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute in Pune for a Ph.D.

You’ve been a journalist for a major portion of your working life. How did you choose journalism when your natural inclination is towards archaeology?

I trained and worked as a journalist for over 25 years in Nagpur and Mumbai. Due to some domestic problems, I had to abandon my Ph.D. and take a short break from my studies. The break grew longer and longer and the opportunity to resume almost never came back until in 2012, after a gap of 30 years – I came across Mugdha Karnik, director, Centre for Extra Mural Studies (CEMS), Mumbai University and Dr Kurush F Dalal, who teaches archaeology there.

And I simply got sucked into it, to join the one-year certificate course in archaeology with them!

Meanwhile, I’d taken up journalism for a living, and I am not too sorry about it as journalism gives one an exposure, vision and perspective that no other profession does. And come to think of it, journalism is reporting on the present and history/archaeology is reporting on the past: small difference!

How did you start making archaeology-related cartoons?

One tends to trivialise the art of cartooning till a cartoonist is thrown into jail! While at the Free Press Journal I had seen Pradeep Mhapsekar at work and had realised the enormous intellectual effort that goes into creating a single cartoon. I was fascinated by it and tried some amateur cartooning. In a contest for women cartoonists declared by the Marathi daily Loksatta I won a consolation prize.

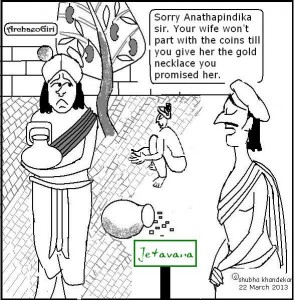

Later, being in a PR company, I made some PR-related cartoons. What really triggered the archaeology-inspired cartoons was the robust, overabundant sense of humour with which Dr Kurush Dalal spiced up his lectures for us. Laughter began to burst through the cracks in academics and ArchaeoGiri (the Facebook page that Shubha uploads her archaeo-cartoons on) was born!

Are there many people who draw cartoons like you do?

No. At the international level, there are cartoons galore on Greek and Egyptian histories. Well-known characters – Noah, Moses, Cleopatra, Archimedes – all have meekly surrendered to the swish of the cartoonist’s pen. There is a whole Asterix series cocking a snook at the mighty Romans. Cartoons on the Stone Age and cave men too are plentiful, but none reflect the features that are specific to the Stone Age in India.

Why can’t we stick a tongue out at Kautilya, pull Anathapindika’s leg, make fun of the globe-trotting Aryans and the seafaring Harappans? Perhaps because we don’t know these people well enough, we need to. Familiarity will breed banter. Perhaps because we take ourselves and our past too seriously although nobody else does. Our ‘feelings’ get hurt at the drop of a hat. Through ArchaeoGiri I have tried to pull historical figures out of boring textbooks and seat them at a modern Indian’s chai-nashta table for a hearty gupshup session.

What are some of the excavation trips you have been a part of?

I’ve been to Sringaverpur in UP and Inamgaon in Maharashtra. Shringaverpur was identified as a ‘Ramayana’ site and excavation was undertaken there under BB Lal. Inamgaon is a pre-iron age site near Pune where extensive work was done by Deccan College for about a decade.

If one wants to study the subject, what are the research tools available as of today?

It is essentially a postgraduate course, being offered at several universities. For lay enthusiasts in Mumbai, I would strongly recommend the certificate courses being run by the CEMS.

What is your comment on the current state of archaeology studies and research?

At a personal level, those who are teaching me archaeology today would have been my students, had I continued my studies, but I have no regrets there. With their knowledge and scholarship, I feel honoured to be in their company as their student.

At another level, however, no country could be richer than ours in terms of archaeological wealth, and no people could be more callous and apathetic towards it. So enormous is this wealth that it can become a perennial source of infotainment, jobs and revenues, but we treat it with the utmost contempt. The state of explorations, excavation, publication, conservation leaves much to be desired. There is a strong case for public archaeology, but that can’t happen without political will and financial support. Despite the excellent work being done at CEMS, it has still not been possible to set up a full-fledged archaeology department there.

What’s on your archeo-wish list?

I would like a James Prinsep for the Harappan script. An Alexander Cunningham for every bit of architecture-sculpture lying orphaned in the wilderness.

A small museum at every district headquarter. A job for every archaeologist. A tool that can date stone artefacts. And equipment that can see underground.

(Shubha’s picture courtesy Pradeep Mhapsekar. Cartoons courtesy Shubha Khandekar)