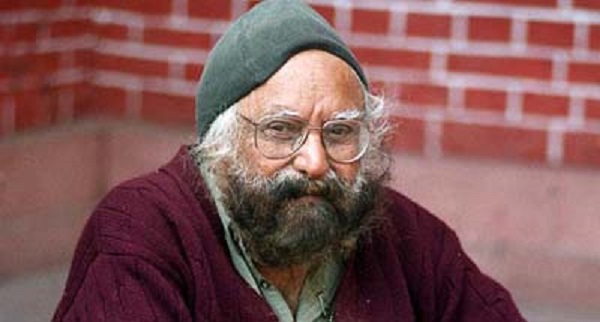

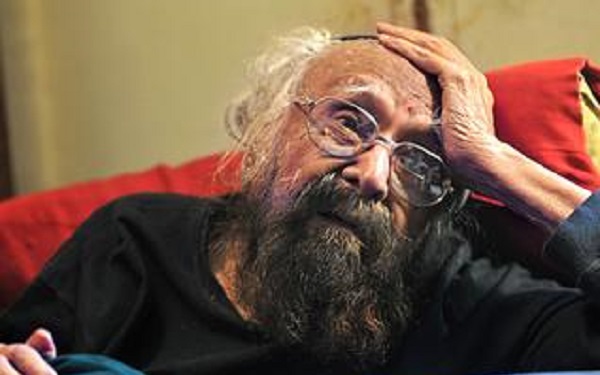

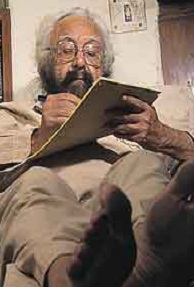

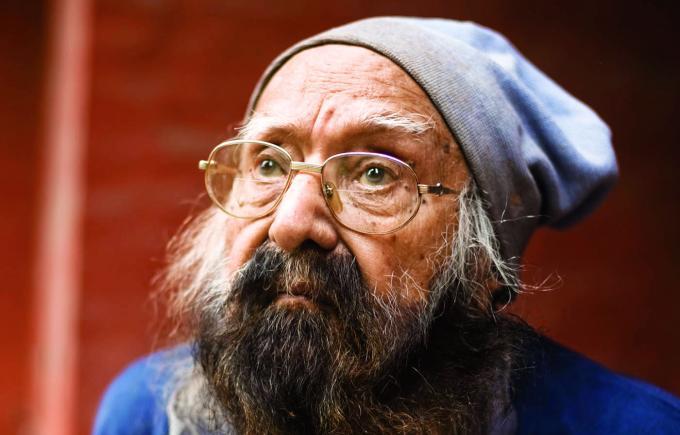

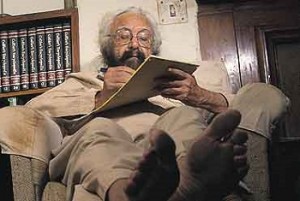

The late author had very stark views about death, and had initially wanted a burial next to a peepul tree.

by Humra Quraishi

by Humra Quraishi

When my father passed away in the winter of 1995, it took me almost six months to recover from the emotional trauma of it all. Now that my dear friend and mentor Khushwant Singh is dead, I really don’t know how long it will take me to recover.

I keep thinking of his words, his stark views on life and death, and everything in between. His views on death were somewhat disconcerting. He would say, “We do not talk of death in our homes, with our families, our children…it is regarded as tasteless, ill-mannered and depressing. This is the wrong way to look at an essential fact of life, which makes no exceptions. I see death as nothing to be worried or scared about. In fact, I believe in the Jain philosophy that death ought to be celebrated. When the time comes to go, go like a man without any regret or grievance against anyone.”

Allama Iqbal expressed this same sentiment beautifully in a couplet: ‘You ask me about the signs of a man of faith / when death comes to him, he has a smile on his lips.’

Khushwant would readily admit that he thought of death often. “I don’t know the answers,” he would say. “I don’t believe in the Hindu rebirth and reincarnation theories. As far as I’m concerned, I accept the finality of death. We do not know what happens to us when we die. We must bear in mind that death is inevitable, be prepared for it.

“Often I tell bade miyan (God) the He has to wait for me as I still have work to complete. Yes, I do fear being incapacitated by old age, by high blood pressure, prostrate problems, deafness, loss of vision. What I dread is this thought: what if I go blind or stone deaf or have a stroke? If that happens, I’d rather die…”

“Often I tell bade miyan (God) the He has to wait for me as I still have work to complete. Yes, I do fear being incapacitated by old age, by high blood pressure, prostrate problems, deafness, loss of vision. What I dread is this thought: what if I go blind or stone deaf or have a stroke? If that happens, I’d rather die…”

Not content to write his own epitaph, Khushwant had also written his own obit in 1943 – this was later published in a collection of short stories titled Posthumous. It read, “I am in bed with a fever. It is not serious. In fact, it is not serious at all, as I have been left alone to look after myself. I wonder what will happen if the temperature suddenly shoots up and I die. That would be really hard on my friend.

“Perhaps, The Tribune would mention it in its front page with a small photograph. The headline would read, ‘Sardar Khushwant Singh dead’. And then in smaller print, ‘We regret to announce the sudden death of Sardar Khushwant Singh at 6 pm last evening. He leaves behind a young widow, two infant children and a large number of friends and admirers to mourn his loss. Amongst those who called at the late sardar’s residence were the PA to his Chief Justice, several ministers and Judges of the High Court…’”

He was also very keen on a burial, wanting to be buried in a corner of a graveyard with a peepul tree next to the grave site. “A burial, because you give back to the Earth what you have taken from it,” he often explained. “Now it will be an electric crematorium. I had requested the management of the Bahai faith if I could be buried. Initially they agreed but then they came up with all sorts of conditions and rules. They had also agreed to my request to be buried in a corner, but later they said my grave would be in the middle of a row and not in a corner. I wasn’t okay with that – though I know once you are dead it makes no difference. They also later said that they would chant some prayers…I couldn’t agree with this because I don’t believe in religion or religious rituals of any kind…”

Humra Quraishi is a senior political journalist based in Gurgaon. She is the author of Kashmir: The Untold Story and co-author of Simply Khushwant.

(Pictures courtesy www.christianmessenger.in, www.outlookindia.com)