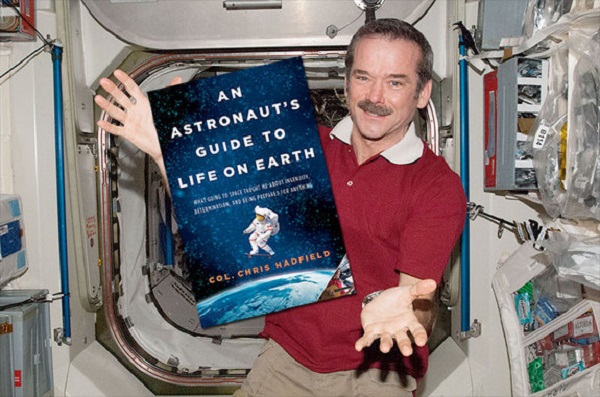

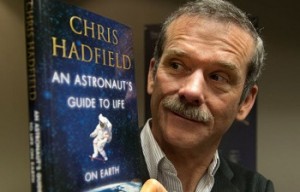

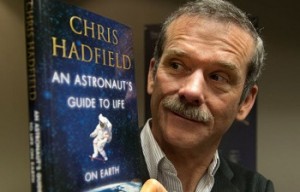

Chris Hadfield’s account of his astronaut life is a must-read for those looking to be (literally) transported to another world.

by The Editors | editor@themetrognome.in

Growing up, a lot of us dream of being astronauts, just like we also dream of being actors, entertainers, doctors and truckers. Growing up, any job that lets us play with toys and props is cool.

Famous astronaut Chris Hadfield, however, held on to his childhood dream of being an astronaut close to his heart. In his book, An Astronaut’s Guide To Life On Earth, the former astronaut and one of the world’s most accomplished persons in his field, describes how he first dreamed of becoming an astronaut at age 9 while living in his native home town in Ontario, Canada. But like most other children who grow up and relinquish their childhood dreams for more realistic pursuits, Hadfield saw his dream through to a hugely successful, trail-blazing glory.

Hadfield describes in humorous, engaging detail how he first dreamed the astronaut dream, after watching the telecast of Neil Armstrong descending on the Moon: ‘Slowly, methodically, a man descended the leg of a spaceship and carefully stepped onto the surface of the Moon. The image was grainy, but I knew exactly what we were seeing: the impossible, made possible. The room erupted in amazement…Somehow, we felt as if we were up there with Neil Armstrong, changing the world.

Hadfield describes in humorous, engaging detail how he first dreamed the astronaut dream, after watching the telecast of Neil Armstrong descending on the Moon: ‘Slowly, methodically, a man descended the leg of a spaceship and carefully stepped onto the surface of the Moon. The image was grainy, but I knew exactly what we were seeing: the impossible, made possible. The room erupted in amazement…Somehow, we felt as if we were up there with Neil Armstrong, changing the world.

‘Later, walking back to our cottage, I looked up at the Moon. It was no longer a distant, unknowable orb but a place where people walked, talked, worked and even slept. At that moment, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. I was going to follow in the footsteps so boldly imprinted just moments before. Roaring around in a rocket, exploring space, pushing the boundaries of knowledge and human capability – I knew, with absolute clarity, that I wanted to be an astronaut.’

It is with the same clarity that Hadfield outlines the agonies and the ecstasies of his journey as a Canadian boy hoping to catch a break into NASA space programme, enrolling in military service to ensure a route to NASA, getting his glider license at age 15, turning down an opportunity to become a commercial airline pilot to focus on being an astronaut instead, getting through to the Canadian Space Agency, and finally, getting the break into NASA. He outlines his journey with insights into daily gruelling schedules, maintaining optimum fitness levels at all times (the slightest disorder or illness can get you off the programme), the relentless training and repeat training of a series of tasks as part of simulator exercises, and working with a team as an equal player who does not seek individual recognition but team success.

His stint as Commander of the International Space Station, however, made Hadfield famous all over the globe – not least because of the live streaming of pictures and videos that he engineered for transmission from the shuttle and the live tweets of important events aboard the spaceship, but for his performance (on guitar and without his spacesuit) of David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’, which became an instant hit online.

His book is an insightful look into the travails and joys of being an astronaut – he describes in vivid detail, for instance, about how zero gravity makes everyday, mundane tasks on  Earth, like washing one’s hair or moving from spot to spot, a complete challenge to master. But his story is not just a superstar’s account of life aboard a spaceship and watching over Earth from a thousand miles away; Hadfield details in pitiless detail the amount of repetitive hard work in the course of training, the compulsive drive an astronaut must possess to be a team player, to practice every single task and routine over and over again and to leave nothing to chance when fighting a crisis. As a reader, you can’t help but be inspired, as he explains the mantra of his success, a philosophy he learnt at NASA: ‘Prepare for the worst – and enjoy every moment of it.’

Earth, like washing one’s hair or moving from spot to spot, a complete challenge to master. But his story is not just a superstar’s account of life aboard a spaceship and watching over Earth from a thousand miles away; Hadfield details in pitiless detail the amount of repetitive hard work in the course of training, the compulsive drive an astronaut must possess to be a team player, to practice every single task and routine over and over again and to leave nothing to chance when fighting a crisis. As a reader, you can’t help but be inspired, as he explains the mantra of his success, a philosophy he learnt at NASA: ‘Prepare for the worst – and enjoy every moment of it.’

Hadfield writes simply and with humour, bringing to life the incidents where he disposed of a live snake while piloting a plane, or breaking into the Space Station with a Swiss army knife, or even washing his hair with no-rinse shampoo aboard the spaceship. Readers will understand why being an astronaut is one of the toughest jobs in the world – and why all the hard work is worth it with just one glance at beautiful Earth from outer Space.

Rating for ‘An Astronaut’s Guide To Life On Earth’: 4/5. Buy the book at a discount on Flipkart.

Excerpt from the book:

‘Weightlessness doesn’t feel the same on a huge spaceship where you can move around freely as it does on a tiny rocket ship where there’s nowhere to go. Imagine floating in a pool without water, if you can, then endow yourself with a few superpowers: you can move huge objects with the flick of a wrist, hang upside down from the ceiling like a bat, tumble through the air like an Olympic gymnast. You can fly. And all of it is effortless.

But effortlessness takes some getting used to. My body and brain were so accustomed to resisting gravity that when there was no longer anything to resist, I clumsily, sometimes comically, overdid things. Two weeks in, I finally had moments approaching grace, where I made my way through the Station feeling like an ape swinging from vine to vine. But invariably, just as I was marvelling at my own agility, I’d miss a handrail and crash into a wall. It took six weeks until I felt like a true spaceling and movement became almost unconscious; deep in conversation with a crewmate, I’d suddenly realise that we’d drifted clear across a module, much as you might gently bob around in a pool without really noticing.

The absence of gravity alters the texture of daily life because it affects almost everything we do. Toothbrushing, for instance: you need to swallow the toothpaste – spitting is a very bad idea without the force of gravity or any running water to help stuff go down the drain and stay there. Hand washing requires a bag of water that has already been mixed with a bit of no-rinse soap; squirt a bubble of the stuff through a straw, catch it and rub it all over your hands – carefully, so it clings to your fingers like gel instead of breaking into tiny droplets that fly all over the place – then towel dry.’

(Pictures courtesy www.canada.com, www.nbcnews.com, blogs.windsorstar.com)